Training a Self-Driving Car via Deep Learning

29 Dec 2016

Intro

This project, part of the Udacity Self-Driving Car Engineer program, seeks to train the steering angle of a self-driving car via deep learning. The car is equipped with 3 video cameras (left, center, right), and the simulator provides a training mode, and an autonomous driving mode. The training mode logs driving data (images, steering angle, throttle, brake, speed) at 10Hz. The autonomous mode loads the developed model architecture and weights, feeds images to the model in real-time at 50Hz, and performs control based on the returned steering angle and the specified throttle.

The Data

As a first attempt, custom training data is collected by using a PS3 controller to drive Track 1 multiple times in each direction. Only center images are used for training, and good driving data is supplemented with corrective driving, veering back to center after approaching/crossing the left/right lane markings. While this approach eventually allows the car to complete a full lap autonomously, it relies on collecting extensive (and potentially track-specific) corrective driving data, which would not be possible in a real-world scenario. With the release of the Udacity training data, the code is refactored to use the left/right images instead of corrective driving. This aligns well with the real-world approach taken by Nvidia in End to End Learning for Self-Driving Cars . It also provides a result that generalizes well to other driving environments.

Data Augmentation

Recorded driving data contains substantial noise. Also, there is a large variation in throttle and speed at various instances. Smoothing steering angles (ex. SciPy Butterworth filter), and normalizing steering angles based on throttle/speed, are both investigated. However, it is difficult to gauge the resulting effect on the model. A potential enhancement to the simulator might allow direct playback of recorded data, such that filtering and normalization may be evaluated independently of the model. The Udacity training data maintains a constant throttle, which alleviates some of the noise.

A constant 0.25 (6.25 deg.) is added to left camera image steering angles, and substracted from right camera image steering angles. This forces aggressive right turns when drifting to the left of the lane, and vice-versa. Variable steering adjustment based on the current steering angle is an area for future investigation.

All images (left, center, right) are flipped to provide additional data, as well as to balance the dataset i.e. avoid a bias for going left or right. The steering angle is multiplied by -1 for all flipped images. Images are cropped to remove the top 32 pixels (part of the image above the horizon) and the bottom 25 pixels (the hood of the car). These areas should not be relevant in training the model. Images are finally resized to 64x64 pixels to reduce training times.

There is room for additional image augmentation, but care must be taken to ensure that steering angles are adjusted where applicable. Some parameters for image augmentation are based on tips provided by Vivek Yadav in his excellent blog, which also details additional augmentation approaches.

A sample set of pre-augmented images is shown below:

left, 320x160, steering: 0.129

center, 320x160, steering: 0.129

right, 320x160, steering: 0.129

The corresponding post-augmented images are shown below:

left, 64x64, steering: 0.379

left flipped, 64x64, steering: -0.379

center, 64x64, steering: 0.129

center flipped, 64x64, steering: -0.129

right, 64x64, steering: -0.121

right flipped, 64x64, steering: 0.121

Data Pipeline

The Udacity dataset contains 24,108 images (left, center, right). After flipping images, the total training dataset is 48,216 images. For validation, a couple custom recorded laps are used (3339 images, center only).

New source CSV files are created, with each line containing the image path, the corresponding steering angle (after augmentation), and a “flip” directive. The lines in the CSV files are randomized.

Custom training and validation generators parse the CSV files and serve up batches of images and steering angles in the specified batch size (default 32). This avoids having to load all data into memory at once. The generators additionally perform on-the-fly image augmentation including cropping, resizing, and flipping. Initially, HDF5 files are created (storing all image and steering data in a single linear container) and generators read slices via HDF5Matrix. This approach is ultimately abandoned as the benefits are minimal on SSDs.

The Model

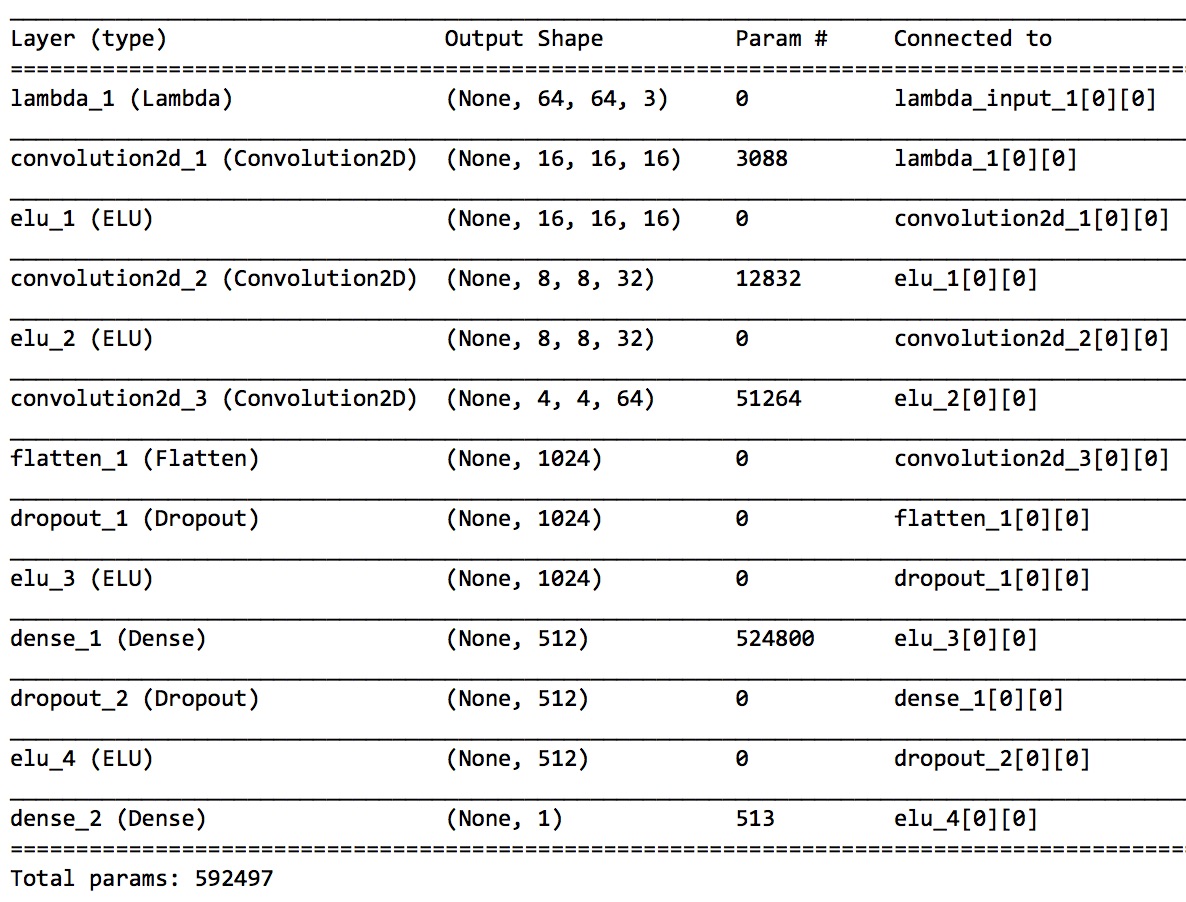

The model uses a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) in Tensorflow/Keras, and is based on the comma.ai train steering model. The model summary is shown below. The input layer takes a 64x64x3 (RGB) image and normalizes the values between -1 and 1 via a lambda funtion. There are 3 convolutional layers using 16 filters of size 8x8, 32 filters of size 5x5, and finally 64 filters of size 5x5. The convolutional layers are separated by activation layers, specificially Exponential Linear Units (ELUs). The inputs are subsequently flattened, and a dropout (0.2) is applied before switching to the first fully connected layer. A second dropout (0.5) is applied before the final fully connected layer of 513 parameters. The dropouts create a robust network that is more resilient to overfitting. The model uses 592,497 parameters in total. Visualizing the convolutional filters, as shown in this Keras blog, is an area for future investigation.

Training

Multiple learning rates are applied with the Adam optimizer, but the default learning rate of 0.001 performs best. Training is run for 8 epochs, and a model checkpoint callback is used to save a version of the model weights at each epoch. The training results are shown below. The training Mean Squared Error (MSE) after the 1st epoch is 0.0327 and it continues to decrease to 0.0194 after the 8th epoch. The validation MSE after the 1st epoch is 0.0277, it drops to 0.0177 after the 5th epoch, and then increases through the 8th epoch. This suggests possible overfitting. Each epoch takes about 4 mins to train on CPU (2014 MacBook Pro). On AWS P2 instances with a GPU, the training time is reduced to under a minute.

Epoch 1/8

32/48192 [..............................] - ETA: 1186s - loss: 0.0587

...

48192/48192 [==============================] - 246s - loss: 0.0327 - val_loss: 0.0277

Epoch 2/8

32/48192 [..............................] - ETA: 42s - loss: 0.0479

...

48192/48192 [==============================] - 246s - loss: 0.0257 - val_loss: 0.0222

Epoch 3/8

32/48192 [..............................] - ETA: 46s - loss: 0.0379

...

48192/48192 [==============================] - 225s - loss: 0.0232 - val_loss: 0.0270

Epoch 4/8

32/48192 [>.............................] - ETA: 154s - loss: 0.0208

...

48192/48192 [==============================] - 216s - loss: 0.0215 - val_loss: 0.0269

Epoch 5/8

32/48192 [..............................] - ETA: 45s - loss: 0.0297

...

48192/48192 [==============================] - 236s - loss: 0.0207 - val_loss: 0.0177

Epoch 6/8

32/48192 [..............................] - ETA: 45s - loss: 0.0292

...

48192/48192 [==============================] - 234s - loss: 0.0202 - val_loss: 0.0242

Epoch 7/8

32/48192 [..............................] - ETA: 60s - loss: 0.0334 - driving_acc: 9.3750

...

48192/48192 [==============================] - 243s - loss: 0.0198 - val_loss: 0.0286

Epoch 8/8

32/48192 [..............................] - ETA: 45s - loss: 0.0323

...

48192/48192 [==============================] - 243s - loss: 0.0194 - val_loss: 0.0343

Results

Applying each set of model weights to the simulator demonstrates that the 5th epoch (which has the lowest validation MSE) actually provides the best driving response. The driving is wavy in nature, which indicates that the core steering angle predictions are far from perfect (to be expected given only a few laps of training data), but this is counteracted by the aggressive avoidance of side lane markers.

Video of real-time simulation running on Track 1:

With minimal tuning of the driving control (additional throttle and a constant increase in predicted steering angles) the model is able to generalize and drive on a completely new track.

Video of real-time simulation running on Track 2:

The project provides great insight into some of the challenges involved in training a deep learning model to control a self-driving car. It demonstrates the critical importance of the collected data (quantity, quality, distribution etc.) and the associated pre-processing/augmentation. It also emphasizes the role of empirical testing in deep learning.

Nvidia has shown that a very similar approach can provide robust real-world results: